Flesh Arranges Itself Differently – Hunterian Art Gallery, Glasgow

English version below

En mars dernier, j’ai eu la chance d’assister à une visite privée de l’exposition Flesh Arranges Itself Differently, en compagnie du Dr Dominic Paterson, l’un des deux commissaires de l’exposition. Exposées dans la Hunterian Art Gallery de l’Université de Glasgow, les œuvres réunies sont issues de deux collections que tout semble opposer. Une partie des œuvres provenait du Hunterian Museum de Glasgow, le plus ancien musée d’Écosse, établi en 1807 grâce au legs du scientifique et collectionneur William Hunter. L’autre partie des œuvres était issue de la David and Indrė Roberts Collection, une des collections privées d’art contemporain les plus importantes du Royaume-Uni. Cette exposition cherche à questionner le rapport au corps et son évolution sociale au fil des années, du siècle des Lumières à aujourd’hui. Le titre de l’exposition, Flesh Arranges Itself Differently, est d’ailleurs issu de La Servante écarlate (1985), un roman dystopique de Margaret Atwood qui questionne la matérialité du corps humain.

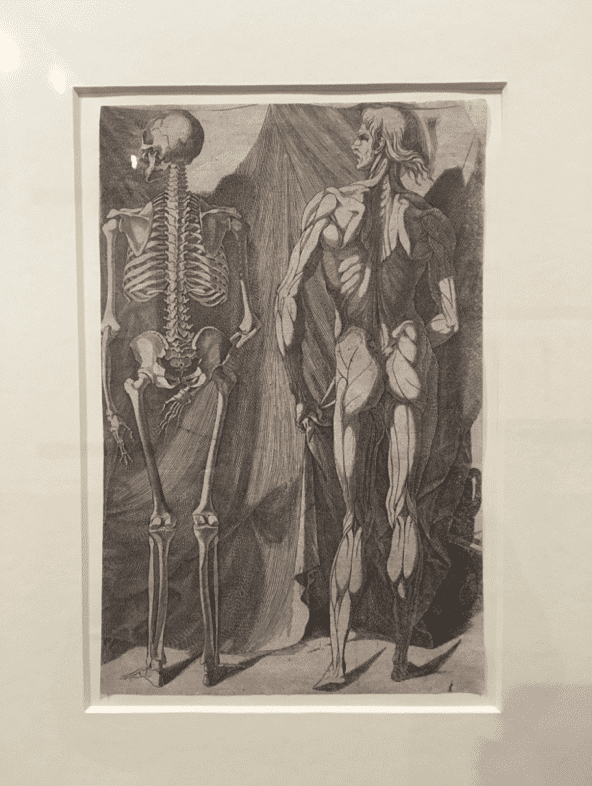

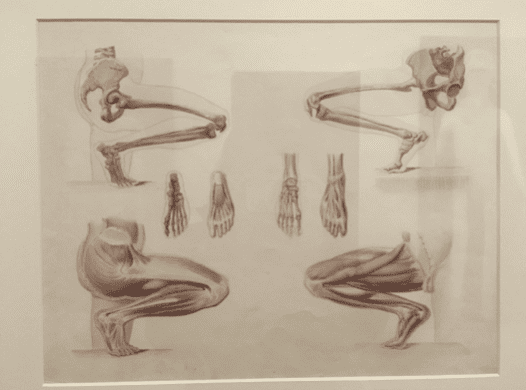

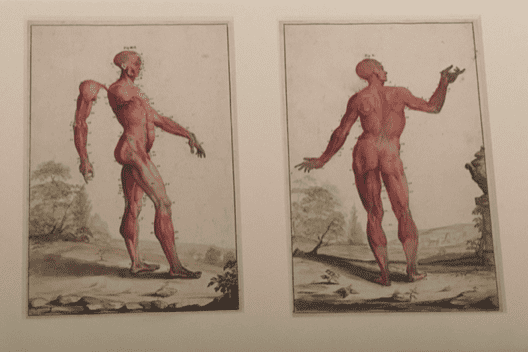

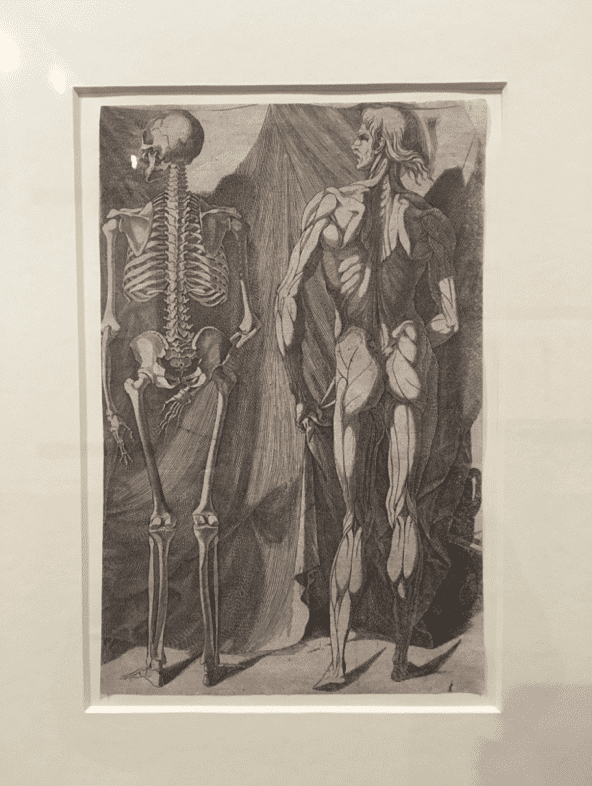

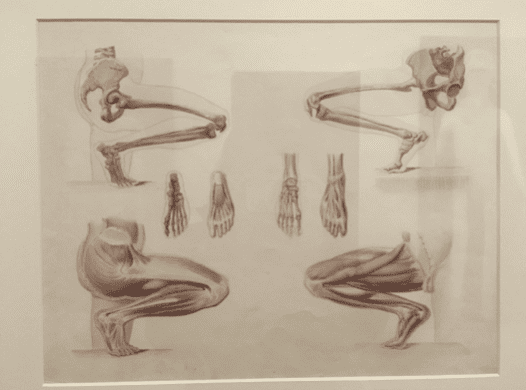

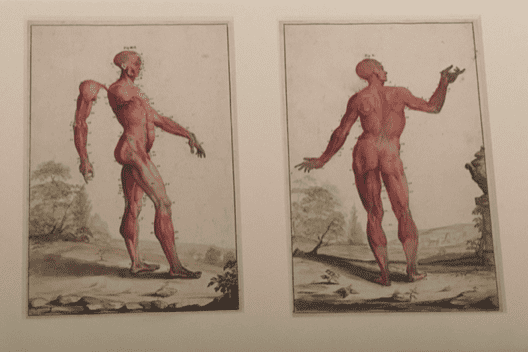

En entrant dans la salle d’exposition, les premiers éléments exposés sont des dessins détaillés de la composition interne du corps humain. Ces études anatomiques sont tirées de la collection de William Hunter, et présentent des caractéristiques communes. La gravure de Domenico del Barbiere (#1) compare côte à côte un squelette et son corps dénué de sa peau. Les études de Stevenson (#2) analysent en détail des pieds et des mains, de leur musculature à leur ossature. Les dessins de Cowper (#3) comportent une numérotation qui permet de légender la décomposition anatomique du corps humain qu’il réalise. Ces trois travaux incarnent un moment clé de l’histoire scientifique de l’humanité. Le corps humain est abordé entre le XVI° et le XIX° siècle comme un objet à explorer, à découvrir, à disséquer. Il est ouvert et découpé en morceaux, depuis lesquels différents tissus et couches sont tracés et analysés avec précision. Le corps humain est considéré comme un élément matériel, qui peut être vu et compris dans son ensemble seulement à travers l’observation cadavérique. Ces projets anatomiques avaient pour but de tirer des conclusions générales sur le fonctionnement du corps vivant, à partir de l’étude de corps éteints. Xavier Bichat, célèbre anatomiste et médecin français, encourageait les curieux à ‘ouvrir quelques cadavres’ dans le but de ‘voir aussitôt disparaître l’obscurité que jamais la seule observation n’aurait pu dissiper’. L’envie d’ouvrir les corps pour mieux les connaitre est également née d’une envie de mieux les contrôler. L’expression scientia est potentia (le savoir c’est le pouvoir / knowledge is power) à longtemps régner sur le monde scientifique, impactant de nombreuses disciplines comme la médecine mais également les questions politiques et sociales.

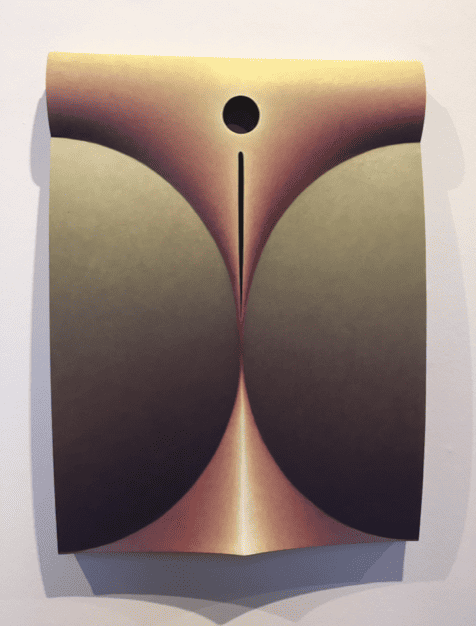

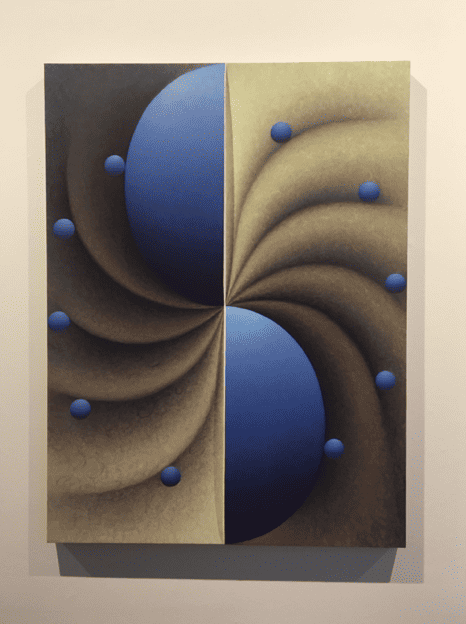

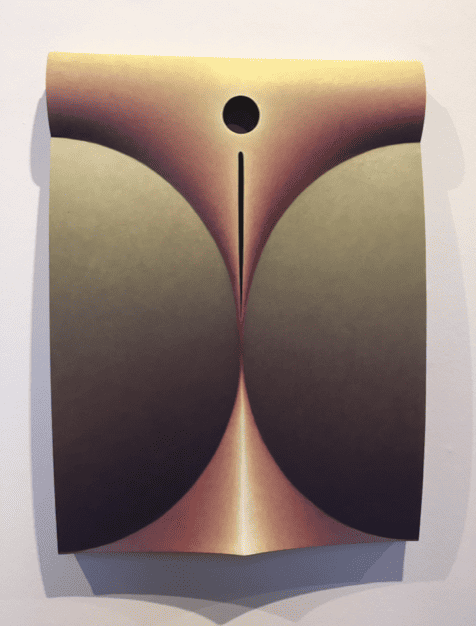

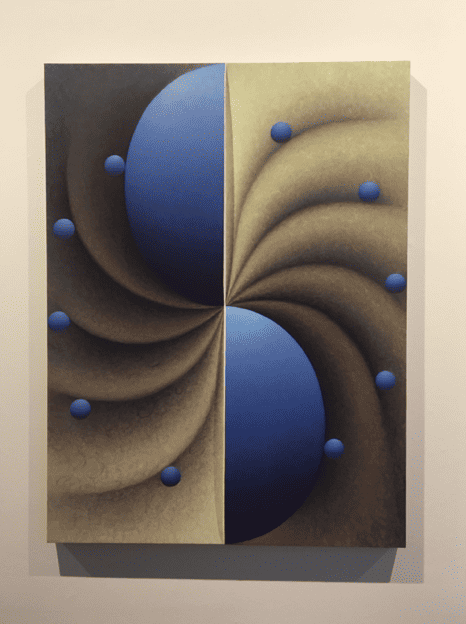

En réfléchissant à ces questions, Michel Foucault, philosophe et écrivain français, en a conclu que la visée exploratrice de la science a impacté le regard que les Hommes portent sur eux-mêmes. En se considérant comme des sujets et des objets de connaissance scientifique, les Hommes ont développé un rapport au corps matérialiste. Flesh Arranges Itself Differently montre que l’expression artistique peut permettre de partager la matérialité du corps autrement que scientifiquement. Les œuvres de Loie Hollowell, Squeezed Cheeks (#4) et Boob Wheel in blue and yellow (#5), présentent des formes gonflées qui sortent de la toile. Ces représentations en 3D ancrent le corps dans une dimension tangible. L’artiste cherche à partager l’expérience sensorielle de l’accouchement en illustrant physiquement des sensations corporelles autrement indescriptibles. Le mouvement répété des courbes représente des pulsations, illustrant les contractions du corps lors de l’accouchement. Les formes bombées exposent les changements physiques du corps des femmes pendant la maternité. La matérialité du corps humain peut donc être explorée et exposée autrement qu’à travers l’étude anatomique de celui-ci.

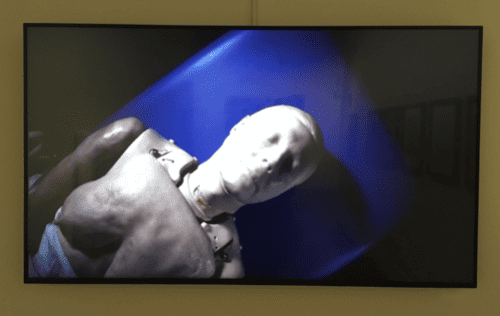

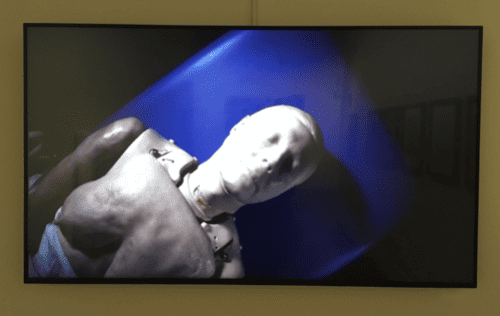

L’artiste écossaise Christine Borland questionne la vision du corps humain comme un objet de connaissance scientifique à travers SimWoman (#7). Ce travail à la fois plastique et audio-visuel complète une trilogie de films dans lesquels l’artiste présente des mannequins utilisés dans le domaine des compétences cliniques (pour préparer les étudiants à la réanimation et aux situations de détresse cardiaque). En voulant réaliser ce film, l’artiste n’a pas pu obtenir ce mannequin féminin car il n’en n’existe tout simplement pas sur le marché. Elle a donc modelé une version féminine du mannequin masculin sur son propre corps en utilisant un moulage en cire. Son film montre les limites de ce modèle ; la poitrine n’est pas bien fixée et les parties génitales sont approximatives. Borland montre que le corps humain comme objet de connaissances est souvent limité au corps masculin. Les dessins anciens présentés dans l’exposition exposent également l’absence de corps féminins. Cette absence peut se révéler dangereuse dans le cas de la réanimation, si les futurs soignants ne sont pas entrainés à réanimer des corps de femmes. Le travail de Christine Borland dénonce le manque de progrès autour du rapport que la science entretien avec le corps des femmes et leur considération dans la société.

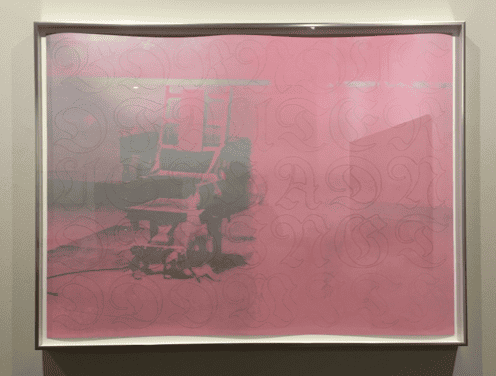

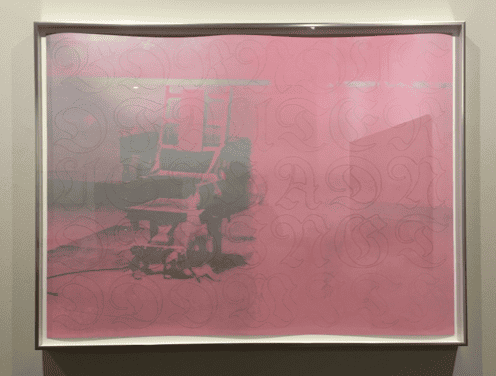

L’exposition Flesh Arranges Itself Differently aborde la question du rapport au corps en excluant l’idée du corps-objet, notamment à travers l’œuvre Sans titre (#8) de Danh Vō. L’artiste superpose une calligraphie gothique sur une impression de La Chaise électrique d’Andy Warhol. On peut y lire la phrase ‘Born Out Of A Uterus I Had Nothing To Do With’ (‘né d’un utérus avec lequel je n’ai rien à voir’). L’artiste considère la question du corps en tentant d’exclure sa matérialité. La chaise électrique est vide, le corps est absent. Danh Vō a dû quitter le Vietnam, son pays d’origine, lors de la guerre Franco-Américaine, pour venir s’installer au Danemark.

La phrase écrite en lettre gothique illustre la séparation du corps et de l’esprit dans la quête d’appartenance. Sa naissance en Asie ou sa vie en Europe ne lui permettent pas de se sentir proche de ces cultures ; le sentiment d’appartenance est immatériel et ne peut pas être rattaché à la condition physique du corps. La vie humaine ne se résume pas au corps et à ses capacités physiques.

J’ai trouvé que cette réflexion résonnait fortement avec l’actualité ainsi qu’avec l’œuvre de Margaret Atwood. La domination de la science a autorisé une vision objectifiante du corps humain, en particulier celui des femmes. En séparant corps et esprit, les femmes ont souvent été considérées comme des machines à procréer. Même si la société occidentale semble avoir progressé sur ces idées, la suppression de la loi protégeant le droit à l’avortement aux États-Unis montre que ces questions sont loin d’être réglées. La capacité du corps des femmes à enfanter est ici séparée du désir, de l’envie de devenir mère et de l’amour porté à son enfant.Margaret Atwood aborde également ces questions dans La Servante écarlate. En replaçant la citation ‘Now the flesh arranges itself differently (…)’ dans son contexte, le lien entre l’exposition et son titre devient plus clair. ‘Désormais, la chair prend des dispositions différentes’ symbolise le changement du rapport au corps. Le personnage principal, Offred, réalise que son corps n’est réduit qu’à un objet et prend ainsi conscience de la matérialité de celui-ci. Les études anatomiques présentées par The Hunterian Museum dans l’exposition présentent le corps comme un objet d’étude, un élément à retourner de tous les côtés pour en comprendre le sens et en retirer une utilité. En créant un dialogue entre des documents du plus vieux musée d’Écosse et le travail d’artistes contemporains, l’exposition montre qu’à travers le temps, les problématiques développées autour du corps humain n’ont pas nécessairement évoluées aussi drastiquement que souhaité.

J’ai vraiment aimé cette exposition ; je l’ai trouvée originale et ambitieuse. C’est toujours rafraichissant de voir des commissaires qui n’ont pas peur d’entretenir le dialogue entre l’art contemporain et des documents plus anciens. Ce dialogue est primordial pour mieux comprendre les inspirations des artistes d’aujourd’hui, et dans le cas de Flesh Arranges Itself Differently, de suivre l’évolution des pratiques artistes en fonction des mœurs d’une époque. Cette exposition permet aussi de réunir des œuvres que l’on n’aurait pas eu l’occasion de voir ensemble autrement. Elle révèle des liens forts entre les pratiques scientifiques et artistiques, et m’a fait réfléchir sur le combat de l’appartenance du corps en société. Néanmoins, j’ai probablement davantage apprécié cette exposition grâce à la visite donnée par son co-commissaire, Dr Dominic Paterson. Ses explications étaient précieuses pour mieux comprendre le propos de l’exposition et expliquer ‘pourquoi’ ces œuvres étaient réunies sous un même thème. Les liens entre les œuvres contemporaines et le thème étaient parfois difficiles à effectuer ; certains objets semblaient ‘compléter’ des trous dans l’exposition plus qu’ils n’apportaient un réel atout à celle-ci. Les légendes explicatives censées apporter des informations supplémentaires à propos des œuvres étaient très minimalistes. Seulement le titre de l’œuvre, le nom de l’artiste et la date de création étaient présent. Paterson nous a expliqué qu’au vu du contexte dans lequel se trouve le musée, au cœur de l’Université de Glasgow, cette exposition était plutôt destinée à des étudiants et professeurs connaisseurs, qui n’ont donc pas ‘besoin’ de légendes explicatives. Cependant, j’ai trouvé cela dommage car l’exposition peut paraître vraiment hermétique lorsque ni les œuvres ni les artistes ne sont connus du public. Cela permet en effet de développer son imagination, et d’essayer de réfléchir aux choix artistiques des commissaires par soi-même. Mais de nombreux visiteurs qui étaient là en vacances, venus avec la curiosité de découvrir cette exposition, ce sont peut-être sentis frustrés du manque d’information à propos des œuvres et du thème. L’essai rédigé par les commissaires et fourni par le musée est très dense et son vocabulaire est complexe. Il permet cependant de rentrer dans la pensée artistique qui a donné naissance à cette exposition et de connaître davantage les artistes exposés.

****

Flesh Arranges Itself Differently – Hunterian Art Gallery, Glasgow

Last March, I was lucky to take part in a private curator’s tour of the exhibition Flesh Arranges Itself Differently, with Dr Dominic Paterson. Exhibited at the Hunterian Art Gallery of the University of Glasgow, the art works came from two different collections that seem totally different at first. Half the works were lent by the Hunterian Museum, the oldest museum in Scotland, established in 1807 thanks to the legacy of the scientist and collector William Hunter. The other half of the works came from the David and Indrė Roberts Collection, one of the most important private collections in the UK. This exhibition sought to question the bodily experience and its evolution through time, from the Enlightenment to today. The title of the exhibition, Flesh Arranges Itself Differently, is a quotation from The Handmaid’s Tale (1985), a dystopic novel written by Margaret Atwood which question the materiality of the human body. Let’s look back at this surprising exhibition, which merges science, politics and fine arts.

When entering the exhibition, the first exhibited works are detailed drawings of the human body internal composition. These anatomical studies belong to William Hunter’s collection, and present common characteristics. Del Barbiere’s engraving (#1) compares a skin-less body and its skeleton. Stevenson’s studies (#2) analyse feet and hands, from muscles to bones. Cowper’s drawings (#3) contain a numerical hierarchy to caption the anatomical composition of the human body. These three works embody a key moment in the scientific history of mankind. Between the 16th and 19th century, the human body is seen as an object to explore, discover and dissect. It is opened and cut into pieces, from which different tissues and layers are traced and analysed with precision. The human body is considered as a material element, which can be seen and understood as a whole only through its cadaveric observation. These anatomical projects aimed to draw general conclusions about the functioning of the living body, from the study of corpses. Xavier Bichat, a famous French anatomist and doctor, encouraged the curious to ‘open up a few corpses’ in order to ‘see the darkness disappear immediately, which observation alone could never have dissipated’. The desire to open up bodies to get to know them better was also born of a desire to better control them. The expression scientia est potentia (knowledge is power) has long reigned over the scientific world, impacting many disciplines such as medicine but also political and social issues.

When reflecting on these questions, the French philosopher and writer Michel Foucault concluded that the exploratory aim of science has impacted the way humans look at themselves. By considering themselves as subjects and objects of scientific knowledge, humans have developed a materialistic relationship to the body. Flesh Arranges Itself Differently shows that artistic expression can enable the sharing of the materiality of the body other than scientifically. Loie Hollowell’s works, Squeezed Cheeks (#4) and Boob Wheel in blue and yellow (#5), feature swollen shapes sticking out of the canvas. These 3D representations anchor the body in a tangible dimension. The artist seeks to share the sensory experience of childbirth by physically illustrating otherwise indescribable bodily sensations. The repeated movement of the curves represents pulsations, illustrating the contractions of the body during childbirth. The rounded shapes expose the physical changes in women’s bodies during maternity. The materiality of the human body can therefore be explored and exposed other than through the anatomical study of it.

The Scottish artist Christine Borland questions the vision of the human body as an object of scientific knowledge through SimWoman (#7). This work, both plastic and audio-visual, completes a trilogy of films in which the artist presents mannequins used in the field of clinical skills (to prepare students for CPR and cardiac distress situations). In the process of making this film, the artist was unable to obtain this female model because there are simply none on the market. She then modelled a female version of the male dummy on her own body using a wax cast. Her film shows the limits of this model; the chest is not well fixed and the genitals are approximate. Borland shows that the human body as an object of knowledge is often limited to the male body. The old drawings presented in the exhibition also expose the absence of female bodies. This absence can be dangerous in the case of intense care, if future caregivers are not trained perform CPR on female bodies. Christine Borland’s work denounces the lack of progress around the relationship that science maintains with women’s bodies and their consideration in society.

The exhibition Flesh Arranges Itself Differently addresses the question of the relationship to the body also by excluding the idea of the body-object, in particular through the work Untitled (#8) by Danh Vō. The artist superimposes French gothic calligraphy on a print of Andy Warhol’s The Electric Chair. We can read the sentence ‘Born Out Of A Uterus I Had Nothing To Do With’. The artist considers the question of the body by trying to exclude its materiality. The electric chair is empty, the body is absent. Danh Vō had to leave Vietnam, his country of origin, during the Franco-American war, to come and settle in Denmark. The sentence written in French Gothic letter illustrates the separation of body and spirit in the quest for belonging. His birth in Asia or his life in Europe do not bound him to feel close to these cultures; the sense of belonging is immaterial and cannot be attached to the physical condition of the body. Human life is not just about the body and its physical abilities.

I found that this reflection resonated strongly with current events as well as with the work of Margaret Atwood. The domination of science has authorized an objectifying vision of the human body, in particular for women. By separating body and mind, women have often been seen as procreating machines. Even though Western society seems to have made progress on these ideas, the removal of the law protecting the right to abortion in the United States shows that these questions are far from settled. The capacity of the women’s body to give birth is here separated from the desire, the wish to become a mother and the love for a child. Margaret Atwood also addresses these questions in The Handmaid’s Tale. By placing the quote ‘Now the flesh arranges itself differently (…)’ in its context, the link between the exhibition and its title becomes clearer. It symbolizes the change in the relationship to the body. The main character, Offred, realizes that her body is reduced to nothing but an object and she thus becomes aware of its materiality. The anatomical studies presented by The Hunterian Museum in the exhibition present the body as an object of study, an element to be turned over from all sides to understand its meaning and derive utility from it. By creating a dialogue between documents from the oldest museum in Scotland and the work of contemporary artists, the exhibition shows that over time, the issues developed around the human body have not necessarily evolved as drastically as desired.

I really liked this exhibition; I thought it was both original and ambitious. It is always refreshing to see curators who are not afraid to maintain the dialogue between contemporary art and older documents. This dialogue is essential to better understand the inspirations of today’s artists, and in the case of Flesh Arranges Itself Differently, to follow the evolution of artistic practices according to the mores of an era. This exhibition also brings together works that we would not have had the opportunity to see together otherwise. It reveals strong links between scientific and artistic practices, and made me think about the fight of bodily oppression in society. Nevertheless, I probably enjoyed this exhibition more thanks to the visit given by its co-curator, Dr. Dominic Paterson. His explanations were valuable to better understand the purpose of the exhibition and explain ‘why’ these works were brought together under the same theme. The links between the contemporary works and the theme were sometimes difficult to make; some objects seemed to ‘fill in’ gaps in the exhibition more than they added a real asset to it. The explanatory labels meant to provide additional information about the works were very minimalist. Only the title of the work, the name of the artist and the date of creation were present. Paterson explained to us that considering the context in which the museum exists, in the heart of the University of Glasgow, this exhibition was rather intended for knowledgeable students and professors, who therefore do not ‘need’ explanatory captions. However, I found that slightly disappointing because the exhibition can seem really hermetic when neither the works nor the artists are known to the public. In a way, it allows viewers to develop their imagination, as they try to think about the artistic choices made by the curators. But many visitors who were there on vacation, who came with the curiosity to discover this exhibition, may have felt frustrated by the lack of information about the works and the theme. The essay written by the curators and provided by the museum is very dense and its vocabulary is complex. However, it allows you to enter into the artistic thought that gave birth to this exhibition and to know more about the artists exhibited.

Sources :

- Xavier Bichat, Anatomie générale appliquée à la physiologie et à la médecine, 1801.https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k98766m/f97.image.r=observation

- The Roberts Institute of Arts, Collection Postcard of Loie Hollowell’s Squeezed Cheeks, 2019.https://www.therobertsinstituteofart.com/programme/projects/collection-postcard-loie-hollowell